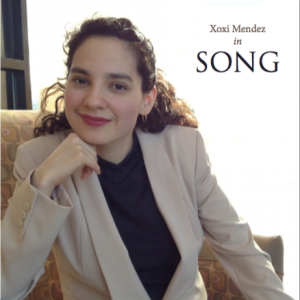

Song is a charming collection of art songs from around the world. It is a journey into the themes of life, hope and endurance on the one hand, and reflections of death on the other.

This is a special collector’s edition ($20). To purchase the CD please contact me individually at xoximendez at yahoo.com. I look forward to hearing from you!

Program Notes:

Track One:

Vaghte on Shod is based on the first two lines of one of Rumi’s poems or  ghazals. In this ghazal the 13th century Persian sage interleaves reaching unity with the divine, with passion, death, and ecstasy—along with the madness that this transfiguration brings (divané shavim literally translates as ‘mad we become’). The poem’s lines are imposing and monumental and Nikan’s music tries to emulate their reach. Though the song features only the first two lines of the text, the remaining lines of the ghazal are indeed formidable: “Spread our wings and pinions like a tree in the orchard, if like a seed we are to be scattered on this road of annihilation. / Though we are of stone, we shall become like wax for your seal; though we be candles, we shall become a moth in the track of your light.”

ghazals. In this ghazal the 13th century Persian sage interleaves reaching unity with the divine, with passion, death, and ecstasy—along with the madness that this transfiguration brings (divané shavim literally translates as ‘mad we become’). The poem’s lines are imposing and monumental and Nikan’s music tries to emulate their reach. Though the song features only the first two lines of the text, the remaining lines of the ghazal are indeed formidable: “Spread our wings and pinions like a tree in the orchard, if like a seed we are to be scattered on this road of annihilation. / Though we are of stone, we shall become like wax for your seal; though we be candles, we shall become a moth in the track of your light.”

Rumi’s poem also has a place for silence, which is represented by Nikan’s very soft vocal and piano passages at the end of the song. Accordingly, the last lines of Rumi’s poem read “No, be silent; for one must observe silence towards the watchman when we go towards the pavilion by night.”

Track two:

Schubert’s Frühlingsglaube /Spring Thought is a song about optimism and hope. It is a song about the beauty of the world during spring, when the processes of nature’s regeneration reach “the farthest, deepest valleys.” In my view, the song can also be seen as the individual’s desire to imbue the private with the beauty of the external. The motion and excitement of a renewing season is represented in the piano accompaniment’s left-hand, where sextuplet notes give a sense of movement and direction—a sense of motion also reinforced by the dotted motif of the right-hand’s chords.

A tinge of longing, nevertheless, is inherent to the song. This can be heard in the rising melodic line of sie schaffen an allen Enden (the blossoms are everywhere) and nun muß sich alles wenden (now everything must change). Renowned pianist Graham Johnson wrote that in this song “the remaining energy of those who have been rebuffed countless times is marshaled to convince the listeners (and themselves) that yes, everything will be all right.”

Track three:

Wanderers Nachtlied/Wanderer’s Night Song exemplifies how, during the Sturm und Drang and romantic periods in Germany, death was seen as an idealized end to suffering. In this song the rising melodic line of the word balde (soon) portrays the patient and optimistic longing for death’s arrival. The piano’s interlude and postlude are very brief yet quite beautiful in their simplicity; their main rhythmic patterns consist of the traditional European rhythm of the funeral march. Perhaps the sublimation of death into peace, that is so pronounced in Lieder, is to an extent an effort to diminish death by casting it as something positive to be longed for.

There is a poignant story behind this song: A thirty-one year old Goethe carved this poem in a cabin in the Kickelhahn woods after a walk in the forest. Fifty years later when Goethe returned as an old man to the cabin, less than a year before his death, upon reading his poem, he wept.

Track four:

Nuit d’étoiles /Starry Night is generally thought as a remembrance of the departed. It makes an interesting contrast to Wanderers Nachtlied and to The Astronomers (track five). Composed by Debussy, Nuit d’étoiles follows the characteristic chanson traditions of brilliance, lightness, and elevation of love. Given that Debussy had yet to settle on impressionism as his primary compositional style when he composed Nuit d’étoiles, some musical critics give this song short thrift. However, this piece is extremely loved by musicians and is a standard of the vocal repertoire—it has even been arranged for chorus. I also find this song marvelous, especially when taking into account that it was Debussy’s first published work (likely composed when he was only a teenager). The piano accompaniment is enchanting—especially during the last refrain when the downward notes in the piano’s right-hand give the impression of falling stars.

Track five:

The Astronomers is a song written in 1959 by composer Richard Hundley. I believe it is a nice song to juxtapose to both Wanderers Nachtlied and to Nuit d’étoiles. The song’s text is based on the epitaph chosen for the grave of Hundley’s own grandmother, Anna Susan Campbell, buried in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. While the vocal line is simple, perhaps to emulate the simplicity of the epitaph, the piano accompaniment is awe-striking. This song movingly makes of the departed astronomers, who in turn “loved the stars too deeply to be afraid of the night.”

Track six:

Nacht und Träume/Night and Dreams is a traditional standard of the Lieder repertoire and is a song about nighttime —about sleep, peace, dreams and stillness. I have always felt, however, that this song is also about longing given the last lines of the text: rufen wenn der Tag erwacht: Kehre wieder, heil’ge Nacht! “[Men call] out when day awakens: Return, holy night! Lovely dreams, return!”

In my view, to Schubert—and this is true of most Lieder in the Romantic era—the authenticity of the self is locked inside in the internal, in exile from the public’s view. Reaffirming this interpretation, for example, in this song, the dreams that “flow like moonlight through men’s quiet hearts” can be seen as an exemplification of the Romantic focus on the person’s inner life.